Rebecca’s Secrets by Robert Hart – extracts

Tommy and his pals explore a basement area of his Gran’s house and find a pile of rubbish she had accumulated.

Among the piles of rotting wood, soggy cushions, and disgusting wet masses of unidentifiable grot, we found a whole armchair and commandeered the cushions for our camp. Under the chair, I found a flat, square box—white, with a silvery floral pattern and something white inside.

It was lacy, folded carefully. It was a wedding veil. Despite being near the bottom of the rubbish, it was perfectly clean—like it had never been worn.

On the back of the box was a scribble: Sylv Angel 44. It said Angel, so it must be something to do with the family, although I couldn’t work out what Sylv meant. Perhaps it was short for silver.

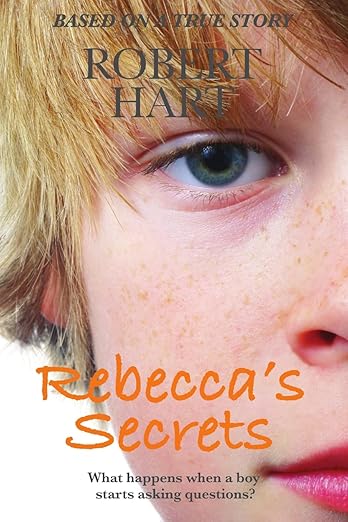

I also found a framed photo wrapped in brown paper. It was of a pretty girl, about four years old.

It was hand-coloured. She wore a red velvet dress with a white scalloped collar. She had blond hair in ringlets, blue eyes, and a big, wide smile. I didn’t know who she was. Perhaps she was Poor Dead Katy. I ran off and hid it with the veil in the air-raid shelter in the backyard. We’d look at it properly another day.

*

Every Saturday night, Gran’s children and grandchildren came around—eleven uncles and aunts and twelve cousins. With Great Aunt Betty, Gran, Granddad, and Tommy, that made twenty-six people crammed into our little basement.

While the men drank beer and became merrier, the women drank gin and became more melancholy. Aunt Marlene sat halfway up the stairs crying, with Auntie Hannah comforting her, while Aunt Nina had a row with Aunt Stella in the kitchen.

Granddad asked me to fetch more ham sandwiches. As I skipped into the kitchen, I saw Aunt Stella sneering at Aunt Nina, whose eyes were red and tearful. Aunt Nina saw me enter and ran out. Aunt Stella twisted round to look at me and snapped,

“What do you want?”

“Aunt Stella, Dad asked if he could have some more ham sandwiches.”

“Haven’t you kids stuffed yourselves enough?”

“No, not for me… for Dad.”

“Little liar,” she said, and her pretty, round face distorted into a sneer.

“Honest, Aunt Stella, Dad sent me!”

“‘Honest, Aunt Stella, Dad sent me,’” she mocked.

“Oh yes,” she said. “Don’t we all know it? Little Tommy—apple of his Daddy’s eye.”

I didn’t understand what was happening. I came in for sandwiches, and now Aunt Stella was angry with me. She suddenly took my ears in both hands and looked straight at me, eyes blazing.

“Well, he’s not your Dad. He’s my Dad, right?

You? You’re a bastard!”

“Why? What’ve I done?”

“Nothing.” She pushed me away with a look of disgust.

“You can’t help it. You were BORN a bastard, and you’ll always be a BASTARD! A bastard son of a WHORE!”

My face flushed, my eyes filled, and my chin started to wobble. I couldn’t understand what I’d done to her. I shouted, “Sorry!” and ran up the stairs, into the yard, and climbed on top of the air-raid shelter, where no one could see me. I stayed there, head in hands, Sobbing until the fire in my head began to subside. I dried my eyes and went to find the only adult I knew I could trust.

Auntie Hannah was with Aunt Marlene on the front doorstep.

She said, “I know, Marl, all men are useless. You can’t trust any of them.”

I took her hand and pulled her into the dark passage.

“Auntie Hannah, I think I’ve upset Aunt Stella.”

“Why?”

“Well, she swore at me.”

“What did you do?”

“I don’t know. I didn’t do anything. Honest. I just asked for Dad’s sandwiches.”

“What did she say?”

“She said he’s not my Dad. She said I was…” I hesitated to say a swear word to an adult, “…a bastard.”

Aunt Hannah looked shocked and angry. I thought it was because I’d said the bad word and that I was in for a good telling-off. But, no—she glared, not at me, but over my head into the darkness of the house and marched away towards the kitchen.

Louis and I ran off to the air-raid shelter. I showed him my treasures: some rifle shells, the gas mask, which he tried on, and then the picture of the little blonde girl in the red velvet dress. I watched his face when he looked at the photo. (He was the first in the family to see it after me.) He turned with his wide grin and said, “Pretty girl.”

“Oi, Louis. What’s a bastard?” I asked casually.

He was younger than me, but at home, he hung around with some rough kids and knew things I didn’t.

“It’s a kid who ain’t got no dad,” he replied just as casually.

Tommy and his cousin Louis hear their grandad singing and run to the living room.

Louis and I grinned at each other. We loved it because it was rude, It made Granddad happy, and it drove Gran wild.

“My wife’s a cow. – a My wife’s a cow.

My wife’s a cow…

keeper’s daughter.

I saw her arse.- I saw her arse.

I saw her arse…

king for water.”

Gran glared at Granddad. The men laughed and joined in the song, and the women tutted and giggled.

I looked for Aunt Stella. She was sitting on the arm of a settee next to Uncle Lionel, scolding Jessica for something, gripping her thin wrist tight.

Someone touched my shoulder. It was Aunt Hannah. I looked up. She smiled.

“Don’t worry, Tommy, she was just a bit merry.

She didn’t mean anything.”

I smiled. If she was merry, why was she so angry? If she didn’t mean anything, why did she swear at me?

“It’s nothing.” She smiled, the way Mrs Green did. “It’s nothing, Tommy.”

But it wasn’t nothing. It was everything.

Then Granddad launched into the song I loved best. I slid into the corner by the coal cupboard, where it was dark, because it always made me cry.

“I leave the sunshine to the flo-wers,

I leave the raindrops – a to the trees.

And to the old folks,

I leave the mem-ory

Of the baby upon their knees.

I leave the moon above

To those in love,

When I leave the world behind,

When I leave the world be —— hind.”

Please, Granddad, Please. Never leave me behind.

One by one, my cousins, with their brothers and sisters, mums and dads, went home and left me behind. Vinny, Gran, and Granddad went to bed. I folded the table away, cleared the chairs to the edges of the room, and opened the put-u-up. I lay in the dark and relived every moment of the evening like it was a play and I was a spectator. I’d always known that I didn’t belong in the family, but I didn’t know why. Apart from Aunt Stella, they were all nice to me, but something was missing. Perhaps, they’d taken me in like a stray puppy, as a favour.

That was it! I was a favour.

I had no right to be there. Louis, Joey, Lucy, and Alice—they all had a right to be there. No matter what they were or what they did. No matter how angry Uncle Sammy got with them, they knew he was their dad and would never leave them behind. Aunt Nina was their mum and would always smile, even when they got into trouble. It was a given, a certainty. Now I saw it for the first time: it wasn’t a matter of choice. They didn’t choose each other; they belonged with each other, and they’d belong always and forever, no matter what. I had a feeling that I didn’t belong, that maybe I was… chosen, taken in like a lost lamb.

And I saw it, for the first time: they could choose to turn me out.

*

After a few discoveries and revelations, Tommy now suspects the wedding veil he found belonged to his mother, and the girl in the photo might be his sister. He remembered seeing a smaller copy of the photo on a visit to his lovely Aunt Hannah. He returns to her, determined to find the truth about his sister, his mother and his father and why his family kept them all secret.

I found a Basildon Bond pad and a Biro and scribbled a note. I left it on the floor outside Gran and Granddad’s room.

Sorry, but I have gone to live with Aunt Hannah.

I was focused on one thing—the little girl in the photo. I was going to find out, once and for all. Aunt Hannah would tell me everything. We’d have that talk she promised.

I stopped at a phone box on Stratford High Street to call Aunt Hannah. She was the first person I’d ever phoned. It was about nine o’clock. I stuffed sixpence into the slot and dialled LOU 5280. When she answered, I pressed button A. I told her I was coming for lunch. I didn’t say I was going to live with her.

My legs were pretty weak after the previous day’s ride, and it took two hours to reach number 57. Throughout the journey, I’d been rehearsing what to say. I opened the iron gate, ran up the path, and pressed her doorbell. But when she opened the door, a shockwave of emotion overtook me.

I forgot my carefully rehearsed script. Tears erupted. I pushed past her and blurted out, “You’ve got to tell me everything, Aunt Hannah.”

I hadn’t meant to be so blunt. I was embarrassed and scared she might be angry. But Aunt Hannah was calm. She followed me into the kitchen, then turned her back to me and put the kettle on. She said nothing. I knew she was embarrassed too, wondering what to say.

“I want to know about that girl in the photo, and about my real mum and dad.” I looked down at the red Formica tabletop.

“No one says anything. I want you to tell me. Please, Aunt Hannah.”

I smudged the tears away. I wasn’t going to cry anymore, in case she thought it would upset me to hear the truth.

“All right, all right.

No need to get upset, Tommy. It’s about time you knew.”

She set the teapot and cups between us, with a little silver bowl of sugar cubes and tiny silver tongs, and a bowl of Nice biscuits.

“I don’t like them,” I said and immediately felt ashamed that my greed had taken over from deeper emotions.

She went to a cupboard and brought a packet of chocolate digestives, which she tipped into the bowl. I blushed. I thought she’d be angry with a boy who put chocolate biscuits before the mysteries of his parenting, but she just smiled and sat opposite me.

She reached over and took my hands gently in hers. No one had ever done that to me—not like that, so gently.

Her hands were thin and wrinkled, but her skin was soft and clean, and her nails were perfectly rounded

with perfect new-moon cuticles.

“The girl is your sister, Carol,” she said, and before she could take a breath, I burst into tears again.

I’d tried so hard not to cry. I was too old to cry like a baby, but I couldn’t help it. A great wailing came from deep inside, from an emptiness I’d felt many times before. I tried to hold it back,

but it was beyond my control. I uttered a loud cry, like a dog mourning its dead master, and buried my face in my hands. Uncle Harry opened the door.

“Any tea?”

He looked at us, froze, and backed out quickly.

I was shaking, breathing in gasps. Even with my eyes shut tight, I could see red everywhere. I stifled my cries and looked up to see Aunt Hannah silently weeping too. She reached across and kissed my forehead, and I remembered Mrs Green’s Purim kiss. She stroked the tears from my cheeks.

“Oh, Tommy! I am so, so sorry. I should have told you before. So many times I wanted to tell you. But Mum said we shouldn’t. I didn’t know what to do for the best.”

Tears rolled down her cheeks, and although I felt it was disrespectful, and I feared it might make her angry, I reached across and stroked her cheek. She angled her head into my hand for a moment

and looked so sad. But then she drew back, sat up, wiped her face, and composed herself.

She spun round, took a big box of Kleenex, and pulled some tissues for both of us.

“Blow your nose, Tommy.”

“I’m sorry, Aunt Hannah. I didn’t mean to upset you. Something came out of me.”

She poured the tea and, using the tongs—not her fingers—plopped two sugar cubes into mine

and slid it across the table, smearing a sprinkle of teardrops over the Formica. She dropped another cube in.

“Just for luck.”

She looked into my eyes and smiled. I knew there were things she couldn’t say that day—or ever. Not about my sister, my real mum and dad. But about her. I felt her love flood over me—more love than an aunt has for a nephew. And then it struck me! That’s why she was the only one with the picture. That’s why she was so upset when she saw it at Gran’s house. So… Aunt Hannah must be my mother!

That’s why she was angry with Aunt Stella for calling me a bastard. That’s why it’s a secret. My aunt is my mother! But… Uncle Harry doesn’t know. That’s why it’s such a BIG secret!